WORD ON THE STREET: Why does this block have 47 manhole covers?

if you're wondering... 47 is a lot

I know that blogs are the type of medium where people only notice when they hear from a writer too much and never when they don’t hear from them enough, but I feel an obligation to apologize for my month-long absence from sending out a post. I’m sure most of you are out living your busy lives, but if any of you are plagued by the deafening silence of this newsletter not being in your inbox in the same way that I have been plagued by guilt for not getting around to writing it, then please accept my sincerest apologies. To those of you have not even thought about this blog once since I last posted, I say, fair.

To explain my absence, I, like most people in my life, will be choosing to blame Trump. As I discussed in previous posts, the widespread axing of federal programs and budgets has caused a chaos spiral in the world of urban planning: in some cases existing projects and grants are being cut, but the bigger issue is the lack of future federal dollars coming to fund city and state projects (and by extension, the consultants like me who work on them). What this means in the short term is that agencies around the country are all releasing proposals at once, getting the work that was funded by the Biden Administration out the door. So we have been in a mad dash to respond to as many as possible before the money runs out, and that’s why I’ve been too busy to write.

But that’s enough insider baseball. What I actually came here to tell you about is the fact that the block few streets over from my apartment has 47 manhole covers on a single block. I first got the tip-off about this from a friend who is working with a water systems non-profit, so I started to investigate. As I walked around counting the manholes, I noticed that not only were there dozens of them, but that they were aggressively sited, including on the sidewalk and even encroaching on some front yards. And for the skeptics out there, I’m not even counting the Con Edison manholes, which are for electric infrastructure and not for water (ConEd is one of the electrical companies in NYC).

Now I know it’s sort of hard to have a sense of these things to understand if this actually a lot of manholes, so I will give you a comparison: the next block over only has 9. So yes, this seems to be a lot. There also are different types of manhole covers with different inscriptions. For example, I saw, “Catskill Water Gates”, “Catskill Water Meter”, “Catskill Water Bypass”, “Catskill Water Manhole”, “DWS”, “NYC Sewer”, and just a plain hexagonal design.

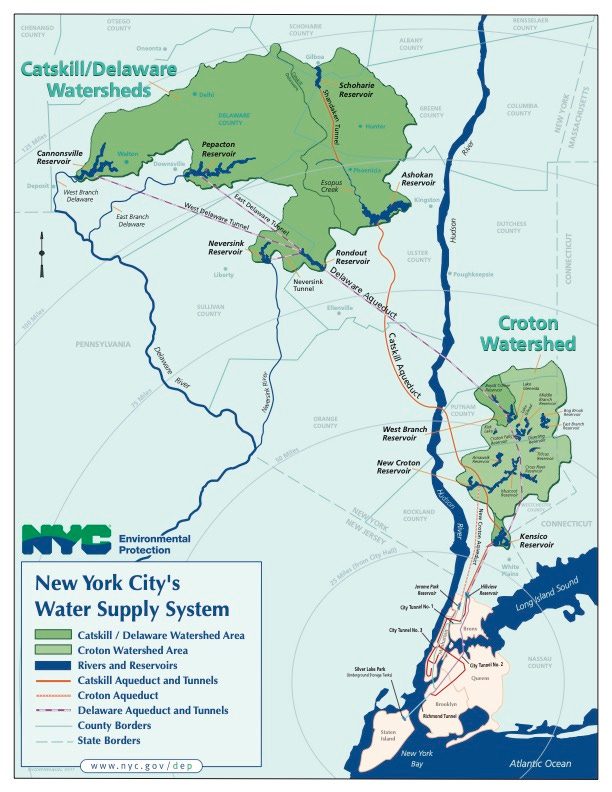

I started doing some research online about what all these different manhole types mean, and while I was able to find information about the abbreviations (DWS = Department of Water Supply), the designs, and a collection of photos of all the different types in NYC, I couldn’t easily find out what makes a meter different from a bypass or a manhole. Even though the information was limited (which I think is related to post-9/11 fears about threats to the water system) we can intuit based on all the references to the water system and the Catskills, that below this block there is some major infrastructure related to the water supply of New York City, a massive system connecting the city to the Catskill and Croton watersheds.

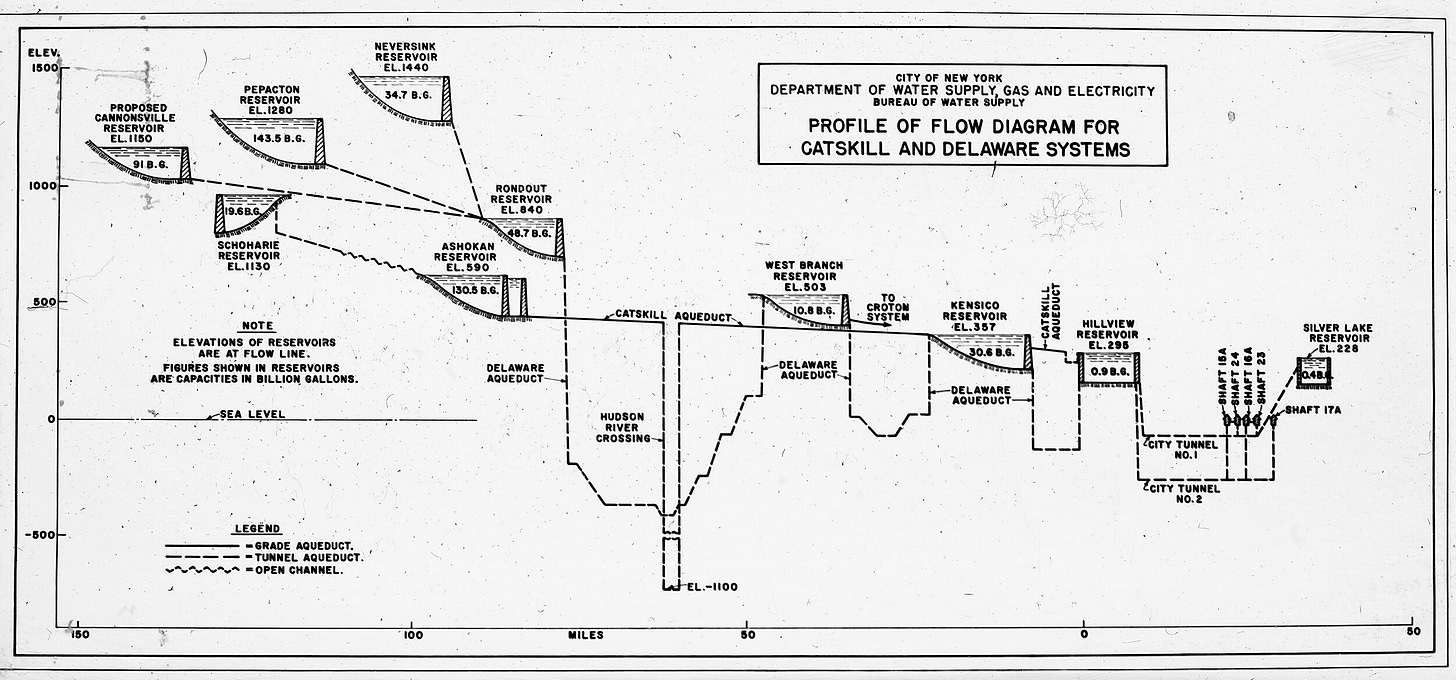

The NYC aqueduct network, which spans over 100 miles, relies 95% on the power of gravity to transfer the water from the source reservoirs to buildings in New York City, with only ~5% of the supply needing to be pumped to its destination. The system achieves this by relying on the same principle that makes siphons work: that a liquid sent through a tube will always return to its source elevation regardless of the path of that tube. Since source elevation of the Catskill and Croton watersheds are far above the elevation of NYC, water is able to travel in tunnels hundreds of feet underground and still return to the surface in the city. In fact, at the point where it crosses the Hudson River, the Catskill Aqueduct reaches 1,100 feet below sea level. Here’s a diagram of the elevation change of the Delaware and Catskill Aqueducts:

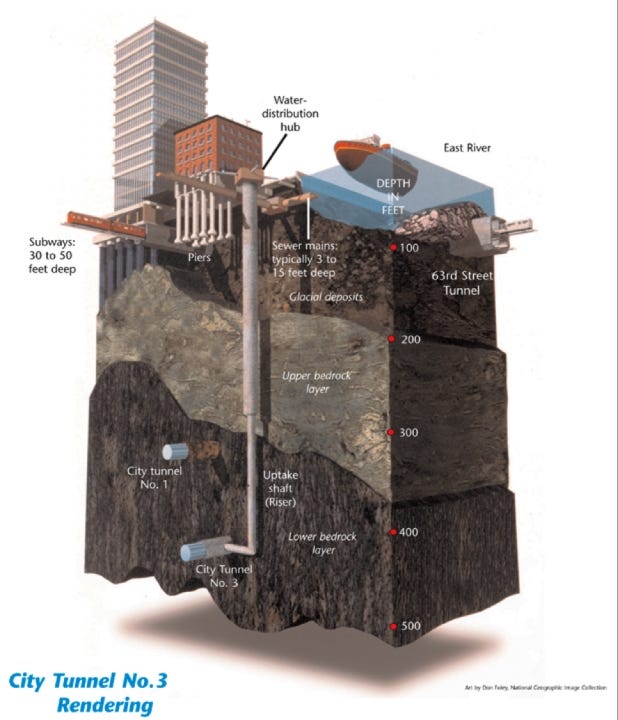

When the water supply reaches the Hillview Reservoir in the Bronx, it is transferred to the “city tunnels” (City Tunnel 1, City Tunnel 2, and the recently completed City Tunnel 3), which are 300 - 500 ft underground and bring the fresh water to its final destination. Here’s a diagram showing how deep that is compared to subways, building foundations, and the East River:

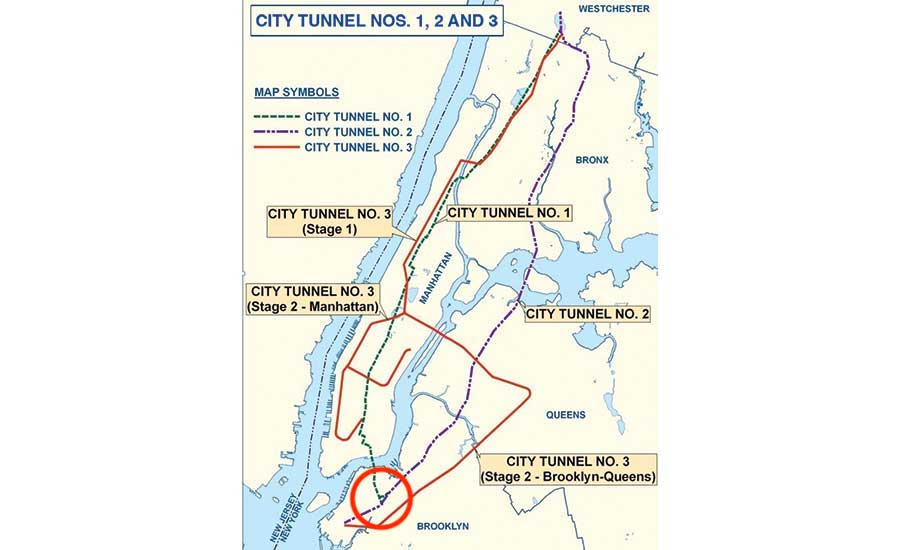

As I was continuing to research the city water tunnels, I found it increasingly hard to find information on the specifics of their routes, and the information that I could find was buried deep in technical documents about the proposals for Water Tunnel #3. So you can consider this search far from over. However, it appears that I may live very close to the point where Water Tunnel #2 reconnects with Water Tunnel #1 in Brooklyn:

I’m not going to reveal the exact location on here because the internet is forever and I don’t want the NYPD knocking on my door, but I’m guessing that these manholes are related to this critical juncture in the water supply system that is essential for providing New Yorkers with safe and healthy drinking water. Or in other words, keeping New Yorkers alive. Water is such a simple and essential part of our existence that it’s rare that we give it any thought. But perhaps there is nothing more important to the survival of the city than fresh water, and though much of the infrastructure that supports it is invisible, it feels profound observe this important node in the massive system of tunnels that travel over 100 miles. It also shows us how something so boring, like manholes, are clues to the systems that support our lives.

I have to end this here because this post has been going on for much too long, but I assure you that I have only scratched the surface of the story of the water supply in New York City and if you’re lucky, there will be more! Here’s some of the things I wanted to cover but didn’t get to: In the 1990s, New York City struck a deal with the counties in the Catskill watershed to limit development to protect the drinking water; there are several former reservoirs in Manhattan, including on Chambers Street and in Sheep’s Meadow in Central Park; the first attempt to fix NYC’s water supply problem was in 1799, when the city gave exclusive rights to supply water to NYC to Aaron Burr’s Manhattan Company - the company did a terrible job of supplying water to the city and was replaced by the Croton reservoir in 1837, but they did use the profits from this venture to start Manhattan Bank, which is the oldest predecessor institution of today’s Chase Bank.

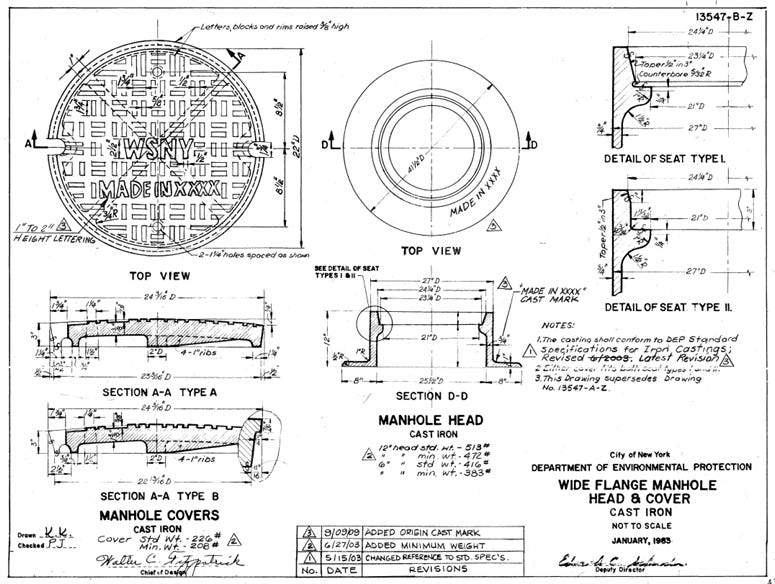

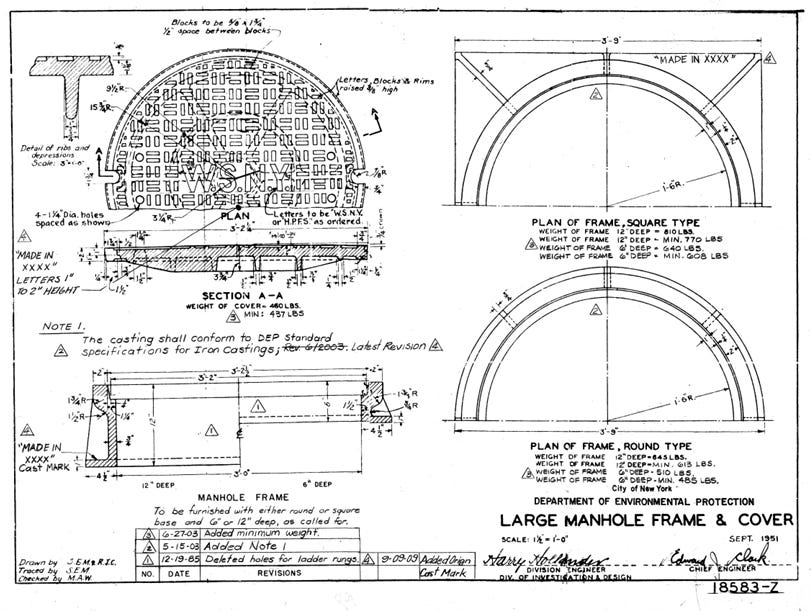

As a parting gift, here’s some engineering drawings of manholes:

Bennett

City Speak #46